One of the most controversial topics. Here’s Stefano’s argument against concentration at pre-seed.

Note from Ryan Hoover: Today, we’re publishing a guest post from friend and GP of Unruly Capital, Stefano Bernardi, on a topic hotly debated in venture.

As I’ve been fundraising for our second fund, I’ve seen a very clear pattern emerging: a lot of LPs seem to believe that to outperform, you need to build an extremely concentrated portfolio (~15–20 companies), and then concentrate follow-on capital in the winners.

The trend seems quite pervasive (aside from a few FoFs specifically targeting diversified funds, shout out February Capital) and I’ve been genuinely surprised by it because the math has been clear for a while: diversified funds have consistently outperformed concentrated ones.

I’m really curious about the reasons for this belief, and will need to dig in a bit more here but one immediate aspect that a few more acute friends have highlighted is surely the enduring appeal of the Great Picker myth. It’s such a better story to believe that someone just has a magic touch, can see the future, can add massive value, is the one who knows all the best founders, and so on, and will therefore translate into a massively higher unicorn hit rate.

I certainly don’t believe that of myself. It would be quite something to believe, given that all the top investors I know have pretty consistent hit rates. They got to the top more as a function of the number of shots they took than the absolute hit rate percentage.

When you look at the actual data, the pattern is very clear: Lowercase I, probably the best-performing seed fund in history, made ~80 investments in Fund I. First Round was doing 20–25 deals per year at its peak. SV Angel placed hundreds of bets. Elad Gil, Semil Shah, Naval, and most others famous SF mega-winners all built high-quality but extremely wide portfolios. Most firms win big by showing up often, and there are rarely any clairvoyants.

Power laws don’t reward magic. They reward surface area.

In any case, given Unruly is built quite differently from what many LPs seem to expect, and I’m sure I’ll have to explain my reasoning quite a few times, I decided to write it down in a clearer way, which can hopefully be helpful to others going through their fund construction models or even founders wanting to understand how different VCs might think and behave.

Variables to think about in fund construction

When building our fund model (and when evaluating my ~30 LP fund investments), I find that I always end up trying to balance together a whole number of factors:

- Check size

- Entry valuation

- (Therefore: ownership — to me ownership is a result and not an input)

- (Therefore: exit requirement)

- X Multiple requirement

- Market coverage

- Competition

- Reason to win

- Follow-on investments

- Deals per GP / Ability to service deals

- EV return per check

- Ability to fundraise a specific fund size

I sometimes feel that when GPs and LPs ask for a concentrated fund model, they miss at least one of these considerations.

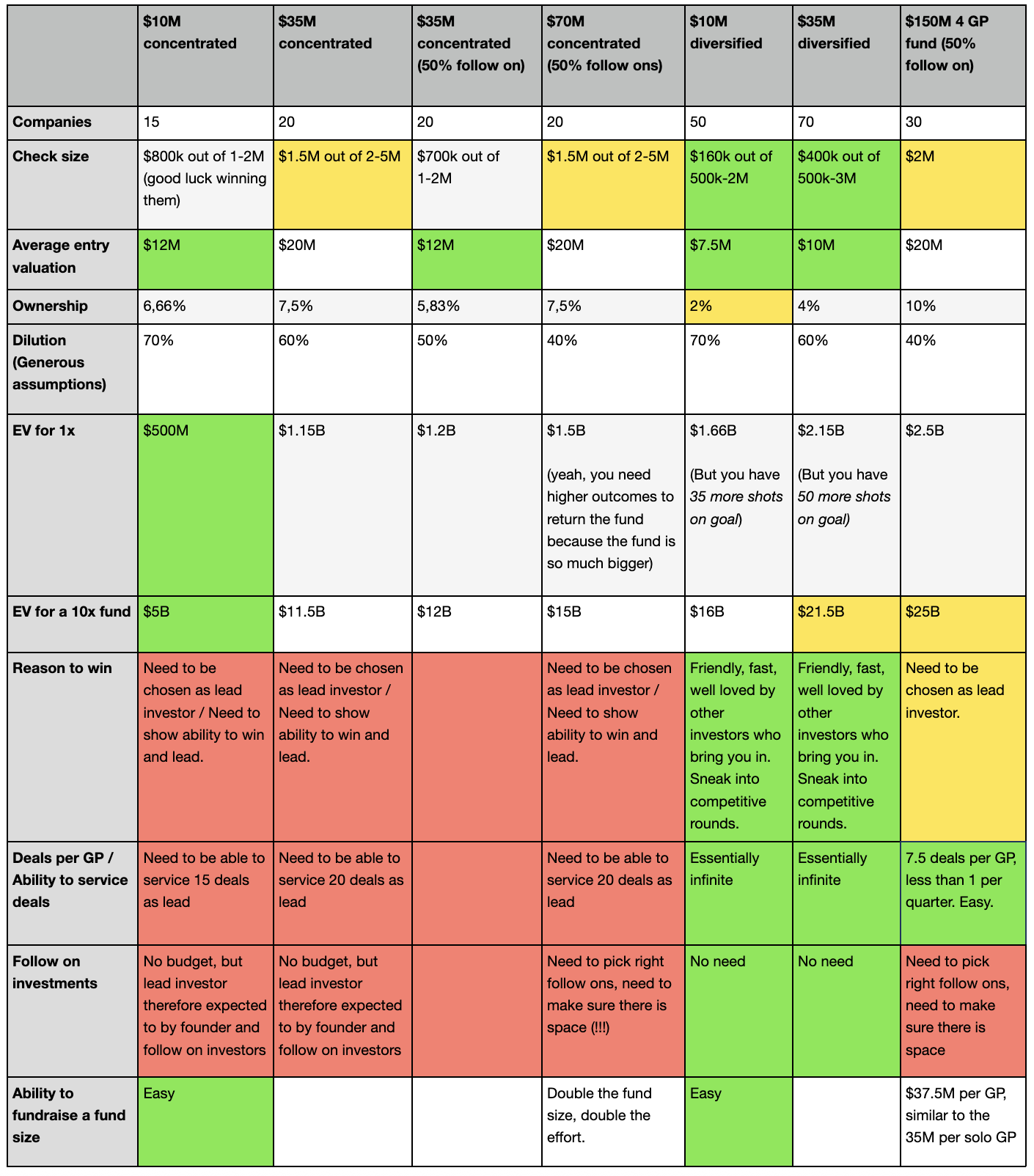

Let’s check out a quick comparison between a few different fund models for smaller, solo-GP funds.

Note: all assume a 20% fee load over the fund’s life.

Note: obviously, this is a pre-seed and seed discussion. Series A funds start to have different dynamics and B and above are a completely different world.

What are the takeaways here?

For me, what jumps immediately to the eye is:

- 10xing a diversified fund is only 2x harder than a concentrated fund, but with a massively higher luck surface area.

Venture is a power law game, we all know that only when you get the really big winner you do very well. If someone offered you 3.5 times more shots for each shot you take and you’d only have to find only a 2x bigger outcome, you’d take the deal every single time.

- If you’re concentrated you’re expected to follow on by the market, but

- follow ons suck and make everything much harder

- You have to raise double the fund size compared to your strategy

- You need to be able to figure out which ones are the right ones (easier said than done)

- You have to win allocations and make sure follow-on investors don’t squeeze you out

- Most especially, YOU NEED BIGGER OUTCOMES.

- Concentrated single GP funds are way harder than they sound.

Maybe you can pull off a 20 lead portfolio if you’re a young fund I and don’t have other time sinks like previous investments, but good luck keeping it up till fund III.

Disclaimer: High conviction investors are awesome

I want to make absolutely clear that I don’t think high-conviction concentrated GPs are targeting worthless strategies.

My main point here is that I believe there needs to be a fundamental self-awareness of what someone’s strengths, setup and specifically reason to win are, and couple all of that with the actual supply of companies “in thesis” that the market will likely produce for the duration of the fund’s investment period.

I’m a happy LP in a few concentrated funds, but I made sure to articulate to myself why I believe they might really have a shot at making it work, and am keenly aware of the higher risk these funds represent in my portfolio.

Unruly’s fund II portfolio construction model

Now let’s walk through what our end portfolio construction outcome has been, informed by all of the above as well as just seeing the market dynamics in the past year.

Unruly’s new fund will have a slightly updated portfolio construction model compared to our original €23.5M Fund I (which will end up with around 70 investments):

Check sizes:

- $250k checks. These can be first-money in very small $300k-$500k pre-seed rounds, or can be opportunistic follower checks into structured $2M-$5M seed rounds.

- $500k-$1M checks: a number of times we got to deals as the first investors, and could have led / put more capital to work. When that’s the case, and there is enough allocation at an attractive valuation, we will lean in and put as much money to work as we can.

It’s very important to note that this has not happened 20-25 times, and we don’t expect it to happen in fund II either, meaning that if we were to only look for larger allocations we would have to lower the portfolio quality, which is unacceptable to me in a power law game.

We project that in the end, the two categories will each account for roughly 50% of the deployed capital.

Reason to win: This strategy is optimized for our ability to win these deals. We’ve demonstrated already that we can write *a lot* of tickets into amazing companies, and we’ve monitored when and how often we could have captured more (and how much) allocation, which we ended up “gifting” to some of our awesome LPs and friendly co-investing funds.

This is much easier than betting we could win 20+ $1.5M allocations, which is a high “venture arrogance” belief.

Entry valuation: The exploratory check size enables us to invest in a lot of $4-10M val rounds + have a few opportunistic checks in $12-20M valuation rounds (and some exceptions to the upside). We expect a $10-12M average here overall, which is in line with what we have in fund I.

We expect the larger checks to come in at $8-12M valuations (we did an $800k @ $8M valuation and are looking at a $750k @ $7.5M valuation).

Ownership and EV requirements: This will yield ownerships of 2-15%, which is a very, very wide band compared to most funds who try to be quite homogenous in their ownership profiles.

Assuming an average 60% dilution over the lifetime of the fund and assuming a $35M fund size, this means we’d need anywhere from $600M to $4B of value to return the fund, depending on which company will be the winner.

If the big winner comes from the exploratory checks, we will be a normal top-quartile fund - remembering that we have an incredibly higher chance of hitting one compared to a concentrated strategy.

If the big winner comes from the larger ticket pool, we will be a 5-10x fund if not more.

This obviously assumes, like every other fund, that we find at least one big winner. (If we don’t, it’s obviously best if I just stop wasting people’s time and money - as well as my own).

Cheating the model (by design)

We’ve cheated a bit here in a sense, meaning that if you’ve noticed we’re trying to get the best of both worlds and have both diversification as well as a bucket of high ownerships. The reasons why should be clear given all of the above, but I think it’s still helpful to list all the questions I’ve asked myself about it:

- Could we build a portfolio of 20 super high quality companies with very large ownerships? I think that’s a very big assumption that a lot of people make too lightly, and I don’t want to make it. We might be able to see them, but winning all of them in the right timeframe and servicing them properly is unlikely.

- Would I be comfortable with just the 10-12 large ticket bucket? Abso-fucking-lutely not. The risk there would be off the charts, without mentioning the bonus topic I kept out of this post, which is all the community / network / learning benefits we’d lose from investing in a large number of companies.

- Wouldn’t it be better to just do the small $250k investments in 50 companies? Yes, probably, but frankly the economics of a $15M fund are not particularly interesting for where I’m at in life and won’t be for anyone else that has shown they can generate returns. (I think this is the optimum for young people starting their fund I with a goal of scaling from there).

- Wouldn’t it be better to just do the $250k tickets but in a lot of companies? Yes, most likely, from a purely math-based perspective, BUT, it is absolutely unrealistic for my bandwidth to think I can build a portfolio of 120 companies in ~3 years. Massive respect for the people who can pull this off operationally while keeping the company quality high, they’ll do very well (and I’m happy to be an LP if a few of these type of funds).

What about Funds of Funds?

The big elephant in the room here is that most of the time we have to view all of this with the lens of allocators that are either full funds of funds, or act as one by having a fairly diversified (10+) portfolio of venture funds.

The rationale that FoFs use is that they are building a massively diversified underlying portfolio of companies and need the VC funds to have high ownerships so as not to have too small of a look-through ownership in the underlying companies, meaning they can still return the full FoF (or a big chunk of it) with one single underlying winner.

We can think of a FoF as a 4-500 diversified fund which charges a bit more fees to be able to achieve such a large portfolio, delegating the actual work to the underlying managers.

I do want to run a full analysis of my thesis here on my 30 LP positions, but the plane is about to land and it might be too math-intensive so I’ll have to do it another time.

In any case, the recap of my thinking around this is that:

- For this narrative to be truly meaningful, the type of underlying VC funds in the portfolio needs to be very, very homogeneous. So this holds for a portfolio of similar size, similar strategy (check size, ownership, stage) funds - but breaks as soon as the underlying funds become a bit more varied.

- The strategy also breaks if for some reason the real vintage winner is not in the underlying funds. At the same time FoFs need massively bigger outcomes for the same strategy to work, and it’s not guaranteed to be able to have proper coverage of a vintage with 10-15 concentrated funds of 15-20 companies.

- If we flip the script and stop looking at the underlying companies, especially if it’s a generalist FoF and we then just look at the opaque funds, a portfolio of optimized funds with low downside risk and potential outperformance would likely not yield meaningfully different results when run through risk modelling algorithms / Monte Carlo simulations. Sure, the downside protection on each fund won’t matter that much anymore, but the higher general EV on each single fund would likely make up for the potential outlier outcome, with the benefit of having an easier-to-build portfolio of funds that are running different and uncorrelated strategies.

- Especially for pre-seed, I believe it’s easier to build a high look-through ownership position in a winner by having multiple funds invested at the lower valuations stacking up smaller positions rather than having one single fund with a large ownership (that will have often required more capital to obtain because of a larger, subsequent round with a higher valuation).

Conclusion

This is far from wanting to be an academically rigorous exploration, and is absolutely not meant to belittle strategies that rely on concentrated fund models.

But I do believe it should help the discourse by pointing the light to a few overlooked “street-smart” situations that oftentimes don’t show up in the nice and clean excel sheets.

“Everyone has a plan: until they get punched in the face” — Mike Tyson

If you’re an LP and GP who has strong opinions in each direction, I’m a venture nerd and these are some of my favorite discussions, so would be super keen to dig in here - especially if there’s any ideas to make our model even more robust. stefano@unrulycap.com

And more about Unruly

At Unruly, we invest in the crazy before it becomes normal. We've been trying to spot developing technological trends for 15 years, and it's worked well: with more than six 100x returners, we hope to have earned the right to continue doing this for a long time.

We are raising our second fund writing $250k-$1M checks. With our first fund, we’ve made investments in quantum photonics, miniaturized MRI machines, molecular glues, robotics protein testing, energy storage, in-space manufacturing, robotic pills and more.

With our second fund, our current top trend we're spotting is the global collapse of fertility and therefore of populations, with a fast-rising need for robotics services as skilled labor retires and aren't replaced. Adjacent areas include fertility and longevity bio, as well as infrastructural and institutional tools to deal with lower populations.

Subscribe to Signature Block

Do valuations matter?

Perspectives from fund managers on the "valuation question".